Originally published in Street Sense Mediaon 27 August 2025

By Annemarie Cuccia / Franziska Wild

In a move that caused shock among the city's residents, especially the homeless and service providers, President Donald Trump federalised the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) and sent the National Guard to the city on 11 August.

In his announcement, Trump, who often associates criminality and the homeless population, classified homelessness and encampments as part of the supposed crime problem in the city. He ordered the security forces to remove tents and threatened to remove people living on the city's streets.

In the days that followed, workers from social projects for the homeless struggled to find safe places for people to sleep, accommodating them in hotels or shelters, while fear, uncertainty and frustration grew.

"You are destroying lives, dreams, livelihoods. You are damaging people's livelihoods," said Temitope Ibijemilusi, who often sleeps in the city centre after being forced by the police to remove his belongings. "They are creating more problems, causing more anxiety."

In total, Street Sense confirmed that at least 20 people have been removed from eight encampments through closures promoted by the federal government. The police ordered many other people to leave public spaces where they traditionally gather. The closure operations were led mainly by security agents, rather than the city's usual social outreach teams.

Despite White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt claiming that 48 camps had been closed since 11 August, the Street Sense was only able to confirm closures at eight locations in the District. The White House has not released a list of locations already closed or upcoming targets.

Meanwhile, data from the city suggests that the number of people living in camps has not decreased significantly in the last two weeks.

Meanwhile, dozens of people sleeping outside have reported harassment, fear and uncertainty due to federal actions and discourse. Although the Trump administration has threatened to criminalise activities such as camping, begging or sleeping outside, publicly available data and data provided by the White House indicate no arrests related to these charges so far.

In response to the crackdown, the city has opened more than 100 additional shelter spaces, according to the D.C. Department of Human Services (DHS), and is prepared to open more if necessary. A second non-congregational shelter is due to open in the coming months, offering new places, and the city will invest more in its homelessness diversion programme.

But not everyone feels safe going to shelters - Kevin, who sleeps outside the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in the centre, finds the shelters crowded and fears getting sick. So he continues to sleep outside. These days, he feels especially vulnerable to police approaches.

"We already know what's going on," Kevin told Street Sense on 19 August, sitting outside MLK at dusk. "I don't know when, sooner or later, but they will come. They're going to come."

The decisive moment

On the evening of 14 August, in front of FBI agents and a crowd of journalists, Meghann Abraham decided that she would stand in front of her tent, arms folded, facing the pressure. She knew she was doing nothing wrong - regardless of what the President of the United States might say.

"Being homeless is not a crime," she told the Street Sense a few hours earlier. "We're not drug addicts. We're not criminals. We have no weapons, nothing. We just want to live."

Abraham, 34, recently graduated from the College of Southern Maryland with a degree in technology applied to national security. She dreams of working for FEMA, helping people in crisis situations. After moving out of the MLK library, she has been living in a tent with her boyfriend on the edge of Washington Circle for the last few months.

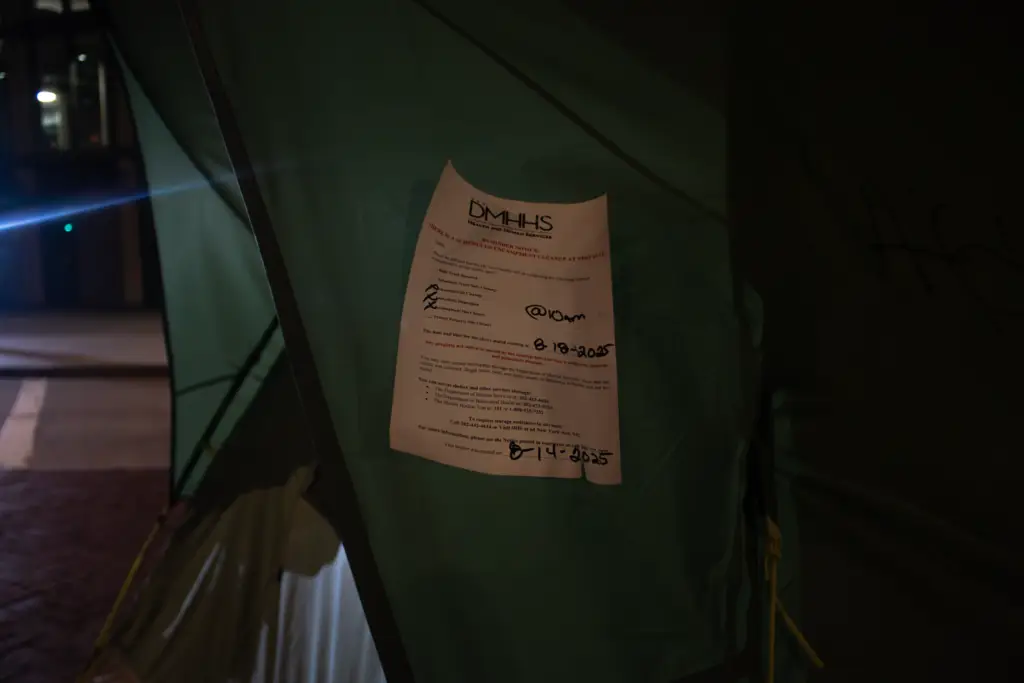

On 14 August, rumours began that federal agents would begin closing down the encampments in D.C. Later that afternoon, the city pasted notices on several tents in Washington Circle, notifying residents that the camp would be closed four days later, on 18 August. At the time, social project workers and local authorities said they were unaware of the sites that would be targeted by federal agents, and were only informed shortly before the FBI arrived.

Shortly after 9pm, at least 12 FBI agents arrived at Washington Circle with the intention of removing several tents, including Abraham's.

When approached, Abraham showed the officers the city's warning sticker. With the support of lawyers, she argued that she had the right to stay until 18 August. The agents eventually left and, although they returned later, they were apparently discouraged by the municipal notice. That night, they closed neither Abraham's camp nor four others nearby that they intended to visit.

However, the departure of the FBI agents was only a small relief. The next morning, local police returned to Abraham's camp and others and closed them down on orders from the federal government.

The agents were first spotted near the Day Services Centre in the heart of the city, where many homeless people go for meals, showers, documents and assistance. Residents and workers reported that agents discarded the belongings of those present. Staff from neighbouring programmes tried to keep people safe by escorting them outside at intervals to ensure their safety during their smoking breaks.

Ibijemilusi recently started sleeping near the centre after the death of the person he was staying with. He told Street Sense that the police forced him to dismantle his tent and discarded other people's belongings.

"A lot of people lost their things today," said Ibijemilusi.

The Metropolitan Police Department then proceeded to the tents near Washington Circle and ordered Abraham to leave under threat of arrest. His boyfriend was working at the time. The police threw away the belongings and tents of other residents, while Abraham tried to contact his friends.

"They asked: is this rubbish? Is it rubbish? And I said that none of my belongings were rubbish. I have these things because I want to have them," she told reporters from the Street Sense who arrived at the time of the removal. "But it's a struggle to defend my rights in the face of 20 police officers."

Members of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) went to the corner of 26th and L, where they removed three tents, displacing at least one resident. They then headed to the centre, where they dismantled a structure at 15th and G streets. There didn't appear to be anyone present.

In total, the police removed at least 11 tents on 15 August - most of them thrown into a Public Works Department truck that was accompanying the operations. The action was led and executed by the MPD, not by federal forces. The office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS), responsible for monitoring and coordinating evictions, was not involved, according to an official statement. O Street Sense also did not record the presence of the usual social support agencies at the closures, with the exception of two DHS employees on 15th and G streets.

"The District had scheduled to close the Washington Circle location on 18 August," a DMHHS spokesperson wrote that afternoon. "However, today, federal officials chose to execute the closure of the site and several others."

Jim Malec, ANC commissioner for the region, said he was outraged by the early closure and worried about a possible alignment of the local government with Trump's orders.

"Promising a deadline of Monday to these people and then destroying their property three days earlier is sheer cruelty, and we need to ensure that those responsible for this decision are held to account," Malec wrote in a statement to the Street Sense.

When the Street Sense called Abraham a few days later to talk about the closure, she described the experience as "violent".

The most recent closure identified by Street Sense took place on 18 August, when MPD agents once again visited the Day Centre area. They stayed outside for about an hour, while social project workers and centre employees helped residents leave. Despite fears that federal officials would be present, the action was conducted by local police and the DMHHS.

A DMHHS official told Street Sense that the operation was "determined by the White House".

A man called Willie Nelson said he was waiting outside the centre in the hope of getting an ID. The centre only distributes IDs on Thursdays and in limited numbers each week, so Nelson was sleeping nearby in order to be seen.

"I'll be first in line," he said.

The state of the camps

D.C. is made up of a mixture of municipal and federal land. Normally, these boundaries determine who closes the camps and which authorities lead the operations.

On federal land, such as the C&O Canal, Rock Creek Park and green areas near monuments and federal buildings, the National Park Service (NPS) has the prerogative to carry out evictions. The NPS and its police have been stepping up repression since May 2024, accelerating the pace in March after executive order of Trump to "make the District of Columbia safe and beautiful".

Between March and the beginning of August, the agency removed 70 encampments, according to Interior Secretary Doug Burgum in a press conference on 11 August. At the beginning of federalisation, there were two camps left on federal land, according to Leavitt in a press conference on 12 August.

The city has its very process of responding to the camps on municipal land, with DMHHS staff responsible for monitoring, social dialogue and, in some cases, removal of the camps. Since the beginning of the year, the city has closed at least 60 encampments, according to a survey by the Street Sense. According to DMHHSOn the initial date of Trump's intervention, there were 62 encampments in the city, housing around 100 people - although many more are sleeping outside on any given night; at least 800, according to the most recent census.

The federalisation promoted by Trump has altered this process. His oversight of the local police (which, even if limited, guarantees federal power over how the police deal with encampments) has made MPD officers removal teams, as part of the attempt to remove the "junkies and homeless" who, according to him, have taken over the city.

"That's his theme, seeing homeless encampments - it triggers something in him," said Mayor Muriel Bowser in a live broadcast on X on 12 August.

The city was the first to initiate unscheduled accelerated closures of encampments, going to the vicinity of the Kennedy Center on 13 August to warn residents to move their tents the next day. (Trump was at the Kennedy Center that same day.)

On 14 August, the city closed the encampment that was initially the target of Trump's indignation in a post on Truth Social, accompanied by photos of tents along the highway with the appeal: "The homeless have to leave, IMMEDIATELY." Following local protocol, the removal was immediate and the residents had just 24 hours to leave the site (the standard is 7 days), making the operation especially rushed.

Rachel Pierre, acting head of DHS, explained that the closure was in response to the August executive order and that other sites could be closed in the following days. Deputy Mayor for Health Wayne Turnage and other city officials suggested that the municipality was better able to coordinate removals, stressing the provision of more services for those affected.

"Closing camps is a very, very complex process, we're dealing with human beings who, in many cases, have been marginalised, their lives are being disrupted," Turnage told the press on 14 August. "We felt that because it was a large site, if it was to be closed, it was up to us to do it," he explained, referring to the seven-tent camp along the motorway.

Social workers had been present in the area since Trump's post, supporting residents on high alert. One of the residents, G., reported to Street Sense on 11 August that he was going to move out that day because of the attention the camp was receiving.

Another, George Morgan, said he hoped Trump and Bowser would come to an agreement. He wanted to fill a newly-opened position in the shelters, but to do so he would have to give up Blue, his beloved dog - municipal shelters don't accept pets.

Despite Morgan's hopes, the closure took place on 14 August. At least one resident agreed to go into shelter; teams offered telephones, temporary accommodation and storage space to others.

During the lockdown, around 12 demonstrators arrived, positioning themselves in the middle of the camp. They held placards saying "being poor is not a crime" and "not having housing is not a crime."

One of the protesters, Reverend Ben Roberts, came from the Foundry United Methodist Church, which helps low-income and homeless people obtain documents.

"The only way to end homelessness is to offer housing. If you're housed, you're not homeless," said Roberts. "We need to invest our resources and leadership in ensuring that - not in this giant 'hit and run' game that only prolongs the problem."

This is the recurring discourse among defenders of the homeless population. Closures may make homelessness less visible, but they don't provide housing. Even those who have gone to shelters in recent weeks (although no numbers are publicised) have not received new federal support that comes close to permanent housing.

In practice, many just seem to migrate. David Beatty spent around six months in the camp on the motorway, moving in after the closure of another camp. He and another resident were thinking of moving to Virginia, where he had lived before, but Beatty was worried about the distance. He has tendinitis, which makes walking difficult and painful.

"I don't know how far the walk is," said Beatty.

Where do people go?

Since the beginning of the federal intervention, the Street Sense recorded the removal of at least 20 tents and the displacement of at least 20 people in evictions - a figure that is probably higher if you consider the evictions of people who don't use tents.

According to the DMHHS, after two weeks under federalisation, there were still 68 encampments in the city, with just over 100 residents. The numbers, almost identical to those reported on 11 August, suggest that instead of seeking shelter, most are simply moving to less accessible locations.

There has been a slight increase in the demand for shelters, according to social project workers and local residents heard by Street SenseHowever, the city has not released figures confirming how many people have sought these places. Some have also been temporarily relocated to hotels by community groups, although they may not stay for lack of resources.

The Street Sense also heard from some people who have decided to move to Virginia or Maryland. Last week, local authorities in these neighbouring states expressed concern about a possible increase in people fleeing D.C.

So far, Hilary Chapman, manager of housing programmes at the Washington Metropolitan Area Council of Governments, which is responsible for the annual census, said that neighbouring municipalities have not registered an increase in homeless people, although it may be too early to judge.

Instead of leaving, social project professionals say that most of them look for more hidden places to shelter.

Edward Wycliff, director of strategic partnerships at District Bridges, reports that the team used to see between five and twenty people per session. Now, it's one or two.

"People are becoming scarce," says Wycliff. It's been harder to find the cared-for, which makes access to services more difficult.

The reality matches the informal surveys carried out by the Street SenseAfter talking to around 70 people over the last two weeks, most said they try to avoid attracting the attention of the police as much as possible. They listed various means, such as avoiding sleeping in exposed places, walking at night instead of sleeping, and frequenting reception centres more. They also say they "behave rigidly" or avoid drawing attention to themselves when they see the police patrolling.

"It's an oppressive situation in which people go into hiding," comments Wycliff. "It also makes it difficult for those who want to help to find someone to offer support."

Fear in the streets

Since the announcement, there has been a climate of fear among activists, workers and people sleeping outside about the risk of criminalisation of homelessness in D.C. Although camping, aggressive begging and other actions are already illegal in D.C., the MPD generally does not make arrests in these circumstances, although some camp residents have been arrested in federal evictions or involuntarily committed.

At a press conference on 12 August, Leavitt said that the MPD would strengthen laws against encampments, allowing homeless people to choose to go to a shelter, receive support for addiction or mental problems and, if they refused, they could be fined or imprisoned.

A Metropolitan Police Department officer handcuffs a resident of a camp held by two other officers, earlier this year. Photo: Madi Koesler

According to White House officials and local and federal public reports, there are still no arrests for homelessness. O Street Sense did not identify these arrests either. But according to sources, the MPD will begin enforcing local laws against hanging out in public spaces. These include D.C. Code 22-1307, which prohibits blocking streets, pavements, building entrances or other passageways, and Municipal Regulation 24-100, which prohibits unauthorised use of public space.

It is unclear how the general increase in police presence has impacted the homeless, who are more vulnerable to prosecution for some offences. At least five homeless people have been arrested since 11 August, all on charges not explicitly linked to homelessness.

For example, the authorities emphasise arrests for "quality of life offences", such as consuming alcohol or marijuana in public. These arrests disproportionately affect homeless people because, by definition, crime takes place in public spaces, which is usual for those living on the street.

The D.C. Hospital Association also reported no increase in involuntary admissions as of 20 August. Prior to the intervention, the D.C. Attorney General's Office sent emails to hospitals in the region warning of a possible spike in admissions if federal agents spread out across the city.

Of the more than 70 people interviewed by Street Sense Over the last two weeks, interactions with the police have been inconsistent. Many report no increase in contact, but others have been approached to show documents or ordered to leave.

For example, a pair of friends reported that at the beginning of 13 August, Secret Service agents woke them up and forbade them to sleep in Franklin Park. Another said that his friend, who used to ask for money on a busy street, has been missing since the intervention began.

In some areas where people traditionally sleep, such as outside MLK, there have been fewer people in recent weeks. Some of those who remain, however, are relatively unconcerned. Several said they believe the police will focus on violent crime, not on people sleeping outside.

Robert Hulshizre said that more agents from social projects passed through the site than police officers. "They already know who's here; it's not like it's a game of hide and seek."

Support professionals fear the lasting impact of the intervention, which can alienate people from social services and create mistrust, making it difficult for them to move into housing in the future.

"The clients we've been able to meet are gripped by fear," says Wycliff. "They've heard and witnessed arrests of people in the community or unknown people on the street, it's frightening for many clients and for social workers."

For those most impacted by Trump's actions, there is a deep understanding of his ineffectiveness in solving the problem. Most have decided to move to other parts of the city. Even those who have accepted shelter have not come close to permanent housing.

Abraham decided to move to another part of the city because shelter doesn't work for her. When asked what she would say to the president - who ordered her eviction and equated people like her with criminals - she emphasised the uselessness of the method adopted:

"In D.C., being homeless is not a crime," he said. "They need to offer us another option, and they're not doing that; they're just telling us to get out of here."

Madi Koesler, Katherine Wilkison, Mackenzie Konjoyan, Nina Calves, e Jelina Liu contributed to this report.

Featured photo caption: Georgetown Ministry Centre's social projects coordinator for the homeless, Ben Zack, helped the only homeless person present at the corner of 26th and L St. NW carry her belongings while the D.C. Metropolitan Police (MPD) arrived at the encampment. Photo: Madi Koesler